Shomari Figures is organizing his campaign in Alabama around issues such as boosting access to health care and protecting the right to vote.

By Brandon Tensley

Shomari Figures meets with voters on the campaign trail. Figures is running to represent the new majority-Black congressional district Alabama was ordered to draw after a U.S. Supreme Court decision last June. (Courtesy of The Committee to Elect Shomari Figures)

On the night of March 20, 1981, two Ku Klux Klan members in Mobile, Alabama, snatched Michael Donald at gunpoint while he was walking back to his sister’s house. He had gone out to pick up a pack of cigarettes at a nearby gas station. The Klansmen beat the Black 19-year-old, strangled him, and slit his throat. They left his body hanging from a tree.

The slain teenager’s mother, Beulah Mae Donald, worked with her attorney and Morris Dees, the co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, to file a civil suit against the United Klans of America. On Feb. 12, 1987, a jury awarded her a $7 million judgment — a sum that was big enough to bankrupt the hate group.

Her attorney was Alabama state Sen. Michael Figures. To him, the money didn’t matter. What mattered was pulverizing the Klan corporate organization to prevent another Black family from suffering as the Donalds had suffered. Now, his 38-year-old son Shomari Figures, who said that witnessing his father’s steadfast commitment to racial justice was “instrumental” and “defining” in helping him choose a career, hopes to keep up the fight as an elected official. A former White House staffer for President Barack Obama, he is vying to represent the new majority-Black congressional district Alabama was ordered to draw after a surprising U.S. Supreme Court decision last June.

Beulah Donald (center) wipes tears from her eyes as she enters the funeral service for her 19-year-old son Michael Donald, who was killed by two Klansmen. The case would later spawn a $7 million civil judgment against the United Klans of America that bankrupted the hate group. (Mark Foley/Associated Press)

“When your father was known for having risked his life to bring down the Klan in the name of general public safety and in the name of Black Americans being able to live their lives free of the threat of violence, then you have to find a way to make people’s lives better as well,” Figures told Capital B.

(He noted that his father received death threats until he died in 1996. Some of those threats came in the form of holiday cards that had sinister messages written within: “Merry Christmas, [N-word]. Just thinking about you,” one card read.)

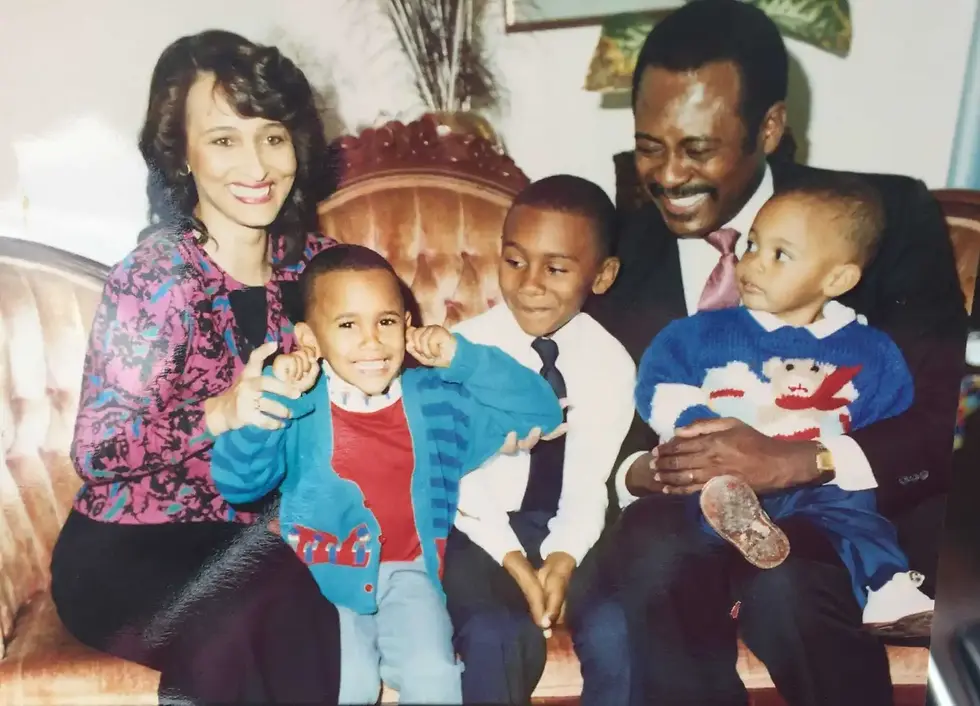

Shomari Figures (secoond from the left) says the steadfast commitment to racial justice by his father, Michael Figures, was instrumental in helping him choose a career. (Courtesy of the Figures family)

Figures is organizing his campaign around issues such as boosting access to health care, revamping the education system, and bolstering voting rights. Black Alabamians have long suffered from poverty rooted in exploitative economic and political arrangements that followed Reconstruction, when “formerly enslaved people were left without any money, property, or other resources needed to be successful,” per a 2022 University of Alabama report. Black Alabamians account for around 42% of residents below the state’s poverty line, though they make up about 27% of the state’s overall population. This contributes to a slew of problems: worse health outcomes, meager labor force participation levels, high unemployment rates, and more.

With the new district, which includes parts of the state’s Black Belt region, Black Alabamians have a fair shot at electing someone who will “bring in resources and create a sense of urgency around community needs,” as Evan Milligan, a lead plaintiff in the Alabama case, told Capital B last June. This greater representation is especially critical in ruby red states such as Alabama, where the interests of Black voters, who lean Democratic, aren’t often reflected in political leaders’ policy choices.

Last fall, Figures left his position as the deputy chief of staff and counselor to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland to join a crowded Democratic primary field; 11 candidates are running. He stands out, he argued, because he’s worked in all three branches of government and knows how these different branches can be used to help district residents. And he added that, unlike many candidates, he lives in the district and is proximate to the issues people care about.

Ahead of the March 5 contest, Capital B spoke with Figures about Black Alabamians’ excitement around the new district, the issues on residents’ minds, and the assault on voting rights that’s gained fresh intensity in recent months.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Capital B: How do Black Alabamians feel about having an additional majority-Black district?

Shomari Figures: Excited. People are very excited about the possibility of being able to put another person in Congress who will actually prioritize the many communities and places that have been overlooked by leadership in the past, certainly in the recent past.

People are really looking forward to going to the polls in March and being able to cast a ballot that actually has the possibility to drive a result that can produce change when it comes to federal focus on the issues in their communities. People are eager and ready to go.

How are you trying to connect with people — what issues are you mobilizing around?

We’re connecting with people by getting out and talking with them and hearing what their concerns are. When you sit down and have these conversations in one-on-one environments or in group settings, you’ll be able to resonate with people.

For instance, in Alabama, we have among the lowest life expectancies in the nation. People in Alabama aren’t expected to live too much longer past their 60s. That’s a mind-blowing statistic: that if you’re born in the state of Alabama, you’re likely to be among the first in the U.S. to die. When you frame that issue through that lens, it resonates.

Everyone in the state of Alabama knows someone who didn’t go to the doctor routinely, so by the time they went, it was too late, and they were dealing with something that was irreversible. For many, if not most, of those people, the reason they didn’t go to the doctor was because they didn’t have access to affordable health insurance, so they lived their lives just kind of getting by medically. Had they been able to go to a doctor, they would’ve discovered that they had something that was very avoidable or reversible.

That story is incredibly common. I was recently in Monroeville — that’s the birthplace of Harper Lee — and I asked people in the room how many of them know someone who didn’t go to the doctor and by the time they went, it was too late. Every hand went up.

And a lot of the issues we have are issues that people struggle with across the country. Our education system needs to be addressed. We need to pay our teachers more. I’m a believer that teaching is the single most important profession for the future of this district and state and country, and we have to treat it that way.

The attack on the Voting Rights Act has intensified since Alabama got a second majority-Black congressional district. What are your thoughts on this supercharged assault on Black voting power?

Unfortunately, these attacks aren’t new. The Voting Rights Act has been attacked in various forms since its inception. For a long time, we were able to rely on the court system to uphold the essence of the Voting Rights Act, but obviously the law took a big hit with 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder decision. I think that a lot of people and entities, including the current leadership in the state of Alabama, saw that decision as an opportunity to go after the Voting Rights Act in its entirety — to gut it and make it meaningless.

Of course, people have fought back successfully. The Alabama case is an example of one of those successes. At the core, voting is essential to democracy, and I feel that, as a country, we should be doing everything we possibly can to make voting easier, more accessible. We should be encouraging the greatest amount of participation we can. But, unfortunately, we’ve seen a faction in this country do the exact opposite, and make voting tougher and more restrictive. That’s real. It’s reflected in the laws and policies passed since 1965 — and certainly more recently.

All of this is a reminder that freedom isn’t free. That the rights that people marched for and bled for and died for across the state of Alabama — Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham — and across the South, we have to continue to fight for them.

Comments